Dallas Observer

April 16, 1987

by Clay McNear

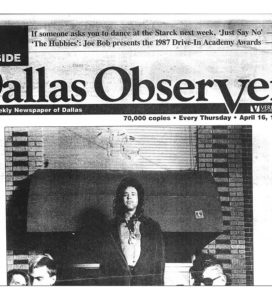

Despite appearances – the shoulder-length chestnut hair that seems perpetually wind-blown, the gleam in the ice-floe blue eyes that belies a fire blazing below, the kooky half-moon grin that can turn oh-so suddenly into a cold snap–Russell David Hobbs is no revolutionary. He didn’t wake up one fine late summer morning in 1984 and decide to change the world, or, for that matter, the future of live music in Dallas, Hobbs just wanted to change his lifestyle, find a place to park his then expansive collection of automobiles, meet some girls. When he opened his art/sage/music showcase hall Theater Gallery in an old warehouse in Deep Ellum in August of The Year of Orwell, he transformed a personal season of discontent into a full-blown Cultural Revolution.

For better or for worse, and there are those who will scream worse, Hobbs’ Theatre Gallery has, in the space of its two and a half year existence, almost single-handedly engineered a major change in attitude toward live entertainment here. Hobbs has, to borrow one particularly cutting Hobbsian phrase, helped to turn a lot of local nobodies into local and regional somebodies, and he has done it by bucking the odds and trends, by knowing what ultra-conservative Dallas won’t accept and then tackling it anyway. His methods have been controversial and non-traditional, his allies few and far between, and his rewards phenomenal. Still, the rewards in question have not been monetary in nature, but artistic.

Theatre Gallery is Russell Hobbs’ artistic triumph of the will. The nightclub intentionally titillates, gambles, and pisses off people. And today, at 28, the ever-bombastic Hobbs has not yet begun to shock. He is equal parts philosopher, womanizer, salesman, cynic, idealist, huckster, guru, he-man, would be rockstar, and cultural outlaw. He steals energy and wealth from the rich and influential and gives it back in abundance to The Great Unwanted: a suburban crowd of TG regulars that consists of mostly open-minded, underground and underage youth boasting little in the way of cash flow. His place, Theatre Gallery, is, as he puts it, “an open sore of culture.” The underground Mecca stands for everything that Dallas doesn’t, and it basically stands alone.

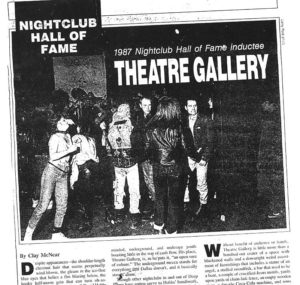

Though other nightclubs in and out of Deep Ellum have gotten savvy to Hobb’s handiwork, bringing in underground bands that TG broke in Dallas and taking aim at TG’s youthful clientele, they are working at a serious disadvantage. The squiggly lines on Hobbs’ fiscal graphs rise and fall to a different beat. Hobbs doesn’t play by the same set of rules as everyone else, and his unorthodox approach to nightclubbing has transformed the underdog Theatre Gallery into the underground kingpin of Dallas. Everything does, as The Byrds and The Bible put it, have a season, and this–love it or hate it–seems to be TG’s. Dallas Observer welcomes Theater Gallery to our annual Nightclub Hall of Fame as a 1987 inductee.

Without benefit of audience or bands, TG is little more than a bombed-out crater of space with blackened walls and a downright weird assortment of furnishings that include a statue of an angel, a stuffed swordfish, a bar that used to be a boat, a couple of crucified-Jesus motifs, yards upon yards of chain link fence, an empty wooden stage, a Day-Glo Coca Cola machine, and rows of faded maroon moviehouse seats acquired from the old Granada Theatre. Sitting backstage in the solemn stillness of the vacant club one recent Wednesday eve, Russell Hobbs is playing host to a most unwelcome sensation.

He’s wrestling with a beat-up rag of a chair, flopping around like a beached tuna. As much as Hobbs loves to talk about himself and claim he doesn’t, he seems positively intimidated by the slight whir of the tape recorder. He bums a cigarette and a match, smokes the cig down to the filter, shivers, and says “Cigarettes make me cold,” then bums another.

It’s a world he never made; this thing called the interview. The “normal” Russell David Hobbs motormouths his weekends away, spewing out the most absurd and wondrous thoughts about (to paraphrase the BoDeans) love and hope and sex and dreams and karma and art and music and tequila while splitting time between TG and his other nightclubs on Commerce, the dank Prophet Bar and Grill and the more romantic environs of The Prophet’s upstairs sister club, Tapaz. But This Russell David Hobbs, trapped helplessly in the here and now, is suffering something akin to brainlock, speaking in fits and starts to get a grip on his thoughts.

“People always go, ‘That will never work. It’s never worked before,'” Hobbs starts off tentatively. “It’s the same thing as Kittyhawk. No one ever thought TG would work or last a long time or anything. But it already has worked and it will, if we want it to, last. Our product is not money in the bank or dividends to our stockholders. Our product is an artist we show then showing at Eugene Binder {Gallery} and selling paintings in Berlin. Our product is a band like End over End that plays here as a bunch of kids just out of high school now having an album and touring across the country.

My intention is to expose people to good art,” He says, attempting to explain TG’s concept, which is basically a symbiosis of painting, music, drama, and free thought. “We’re not the first rebels or the first artists. We’re just doing it in a time when it’s not profitable. I traveled around and I saw people, like, in Mexico City, crawling to the Shrine of Guadalupe on bloody knees to pray, and I saw the art in their galleries. I wanted to bring my hometown things I’ve seen in New York City, Mexico, Alaska. I guess I came to Deep Ellum for adventure, but I wasn’t thinking in terms of opening a nightclub or anything. I’ve always vaguely had visions of owning some amusement park or something. You know, ride a rollercoaster, hear some music, see some films. But you have to work too long for those dollars, so I started working for a different kind of dollars.”

Just as Hobbs is a non-revolutionary who has revolutionized one segment of Dallas nightclubbing, he is an antithesis to the notion of the “poor starving artist” who has come to patronize the starving artist crowd, musically, and otherwise, via TG. Hobbs didn’t become a patron of the arts because he had nothing to lose. Quite the opposite. This raggedy man who goes by nicknames “Tarzan” and “Jungle Jim” hails from a firmly middle-class upbringing in Richardson, and has never really wanted, financially, at least prior to TG. Before he began his new life as a karma-bound hippie in Deep Ellum, Hobbs lived the yuppie Highland Park/North Dallas lifestyle, paying the bills with an enviable income earned as a construction designer and to a much greater degree, with pieces of his soul.

Reformed yup Hobbs now seems to greatly resent his former lifestyle, and those who prefer to hold on to those values. But his goal is not to crucify yuppies; he wants to bring them around to his way of thinking, and his weapon of choice is the TG.

“You know it’s like what {The DMN} said about me” he says, paraphrasing, “This crazy dude in Deep Ellum will let anybody play.” That was our original concept. The frustration of living in an apartment in North Dallas and paying your bills and wanting to get a job and get ahead in this life is ridiculous. It’s a nowhere road.

Dallas is a very, I think, mislead metropolis,” he continues. Masses punishing themselves, thinking they have to keep up with the Jones’s. Something like TG represents promise and future, so that the human race doesn’t go crashing off the same hill in California on a bunch of BMWs like buffalo, following each other and listening to Huey Lewis. And then there’s a guy like me, having a philosophy of wanting to free up the system and wanting to have people share with me that thing of not necessarily being against society, but just for new way of thinking. All you need is a trend and an attitude that makes something gather momentum. Theatre Gallery was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Or, you could say, it was the water that got the camel across the desert.”

Pre-TG, Dallas music had a fairly lame identity. Post TG, Dallas has developed something of a national reputation as a musical oasis for new “cutting edge bands” like Three on A Hill, The Trees, New Bohemians, Rigor Mortis, Rev. Horton Heat, Shallow Reigh, Loco Gringos, End Over End, and The Daylights. While the free wheeling TG can’t take all of the credit for the sudden delirious outburst of music, it certainly helped to open the floodgates.

Hobbs points out that his gallery/nightclub is “devoid of catch 22’s” Unproven bands and playwrights and artists can perform or produce or display at TG without the threat of a financial or moral bottom line hanging over their heads. The bands at TG perform in a style that Hobbs describes as “high energy music with anarchist type lyrics”. Many of the plays would be rated X if they were released intact as motion pictures, and the gallery showings are often crude and more often thought-provoking. TG is the place where New York performance artist Karen Finely bared herself onstage and showed a few Dallasites what you can do with yams if you really put your mind to it. Hobbs describes these separate but similarly minded concepts as “art progression” and much of it, respective to the social mores of Dallas, seems to originate from somewhere in deep left field. Hobbs, for his part, wants to take it further over the edge.

“We’ve got to do what nobody else will do,” says a by-now fully charged Hobbs. We need to push that cutting edge stuff all the time. We’ve found the things that Dallas will not do, those are thing things that TG needs to do. We’re never gonna lose that elemental philosophy we started with; that is, if someone’s knocking on the door and he’s got a tape and we don’t know who he is, we’re still gonna listen to it.

“TG, well, it’s all faith in the future,” he says. “We’re not down here spraypainting the walls and saying the world’s gonna end tomorrow. We’re just young and we have a new way of thinking. TG has been such a phenomenon of culture shock. But we’re not throwing out society’s rules. A lot of those rules are important. We’re just saying the ones that aren’t important, f**k ’em.

“Just believe,” Hobbs says, the sudden cold snap dissipated and that kooky half-moon grin plastered back on, “and don’t disbelieve.”

The revolution lives.